Ignacio Cervantes: The First Virtuoso Cuban Pianist of the 19th-Century Romantic Era

Ignacio Cervantes (1847–1905) sits at the crossroads of European Romanticism and the birth of a distinctly Cuban art-music voice.

Maestro Ramirez Publishing

10/14/20254 min read

Ignacio Cervantes: The First Virtuoso Cuban Pianist of the 19th-Century Romantic Era

Ignacio Cervantes (1847–1905) sits at the crossroads of European Romanticism and the birth of a distinctly Cuban art-music voice. A child prodigy from Havana who matured into a cosmopolitan virtuoso, he fused salon elegance with creole rhythm and Afro-Caribbean cadence—then distilled it all at the piano into brief, perfect miniatures that critics love to call “Cuban Chopin.”

From Havana Prodigy to Parisian Laureate

Born in Havana, Cervantes received early training from Juan Miguel Joval and, crucially, from the composer-pianist Nicolás Ruiz Espadero. When the celebrated American virtuoso Louis Moreau Gottschalk toured Cuba, he recognized Cervantes’s talent, mentored him, and helped send him to Paris. At the Conservatoire (1866–1870), Cervantes studied with Antoine François Marmontel and Charles-Valentin Alkan, earning top prizes in composition (1866) and harmony (1867)—credentials that placed him among the era’s serious musical figures, not merely a salon entertainer.

Virtuoso Pianist, National Voice

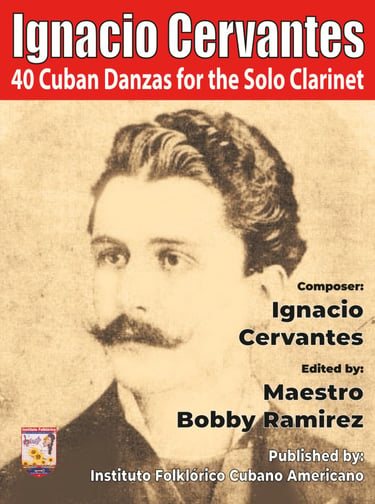

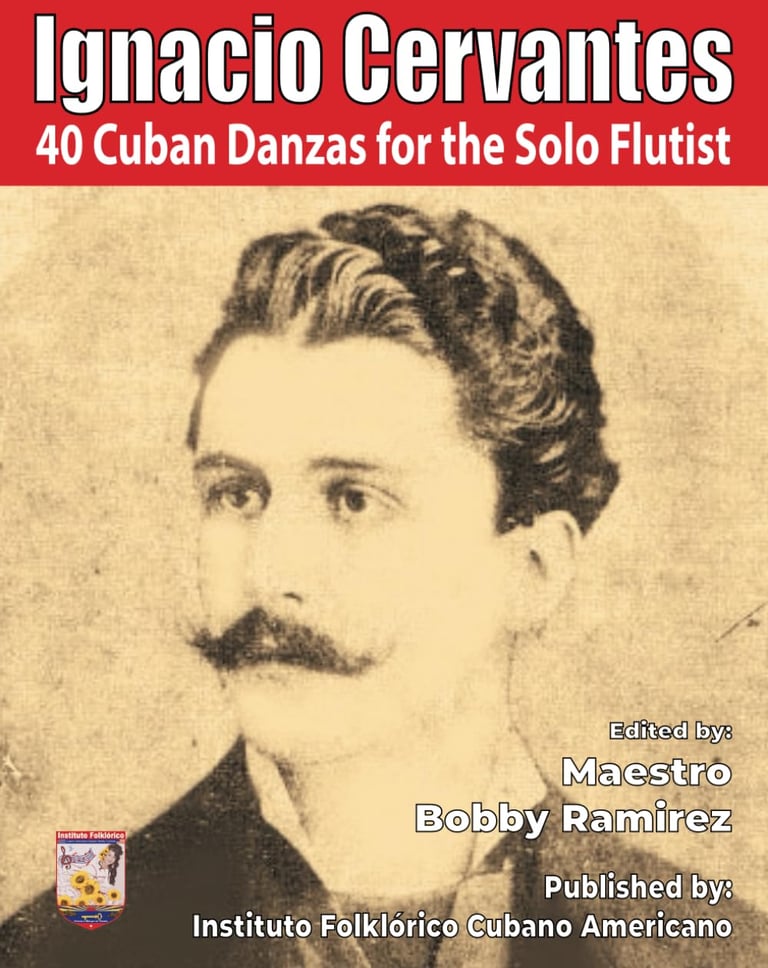

Cervantes returned to Cuba in 1870 as a refined concert artist and pedagogue, but he was more than a touring virtuoso. In compact, lyrical forms—contradanzas and danzas—he embedded Cuban rhythmic DNA (tresillo, habanera lilt) within European phrasecraft. His iconic Danzas Cubanas (commonly cited as 37–41 pieces, depending on edition) remain the cornerstone of 19th-century Cuban piano literature, akin to Grieg’s Lyric Pieces or Dvořák’s Slavonic Dances in national significance. Signature titles like “Los tres golpes,” “Adiós a Cuba,” and “Soledad” show how two pages of music can carry wit, longing, and rhythmic bite.

Salon Miniatures with a Big Idea

Why do these short character pieces matter? Cervantes took the contradanza/danza—social dance forms already “Cubanized” by predecessors such as Manuel Saumell—and elevated them into art-music statements. The left hand often rocks a steady accompaniment while the right hand sings elegant, often bittersweet melodies shaded by off-beat accents and hemiolas. The result is music that feels intimate yet sophisticated, Romantic in its lyricism and unmistakably Cuban in its groove.

Art, Conscience, and Exile

Cervantes’s life also mirrors Cuba’s 19th-century struggle. In the 1870s he and fellow virtuoso José White used concerts to raise funds for independence, actions that led authorities to expel them. Cervantes continued performing in the United States and Mexico, returning to Cuba intermittently as politics allowed. Works like “Adiós a Cuba” have long been read as musical diary entries of exile and yearning.

Technique and Touch

Pianistically, Cervantes rewards a refined legato, supple rubato, and a dancer’s sense of “lift.” The music benefits from pearly right-hand voicing (a Paris-school hallmark) and clarity in left-hand patterns so the habanera/contradanza pulse breathes without heaviness. Think bel canto at the keyboard—phrases that sing—balanced by rhythmic slyness that invites the feet to move (if only in your imagination). Interpretively, letting cadences “smile” (tiny agogic delays), shaping inner voices, and keeping textures transparent will illuminate his cosmopolitan craft.

Influence and Legacy

Cervantes crystallized a Cuban pianistic idiom that later composers and bandleaders would recognize and expand—an essential bridge from salon danza to the danzón era and beyond. His music stands as a model of cultural synthesis: Parisian polish, Havana heart. Today, recordings and scholarly editions have made the Danzas Cubanas a staple in Latin American repertoire courses and recital programs worldwide.

Starter Listening Guide

Los tres golpes – Cervantes’s most-cited contradanza: poised, witty, and rhythmically buoyant.

Adiós a Cuba – a compact gem often read as exile elegy.

Soledad and Picatazos – contrasting snapshots of lyric melancholy and playful sparkle; frequently anthologized.

Why He Still Matters

If you teach, program, or study Romantic-era piano music, Cervantes offers a concise gateway into Cuban musical modernity: pieces short enough for students yet sophisticated enough for professionals; music that sings like Bellini, steps like a habanera, and thinks like Paris. That blend is precisely why Ignacio Cervantes deserves his place among the 19th-century Romantic greats.

#HasIgnacioCervantes #CubanPiano #DanzasCubanas #19thCenturyRomantic #CubanClassicalMusic #Habanera #Contradanza #ParisConservatoire #LouisMoreauGottschalk #ManuelSaumell #JoseWhite #CubanHeritage #LatinAmericanClassical #PianoRepertoire #RomanticEraMusic #MusicHistory #CubanComposer #AfroCubanRoots #HavanaToParis #ConcertProgramming

Maestro Ramirez Publishing

Explore our collection of captivating published works.

Contact:

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Email: